Solar power could be the answer to quick hurricane recovery

Sunrun Team

· 6Expecting the unexpected isn’t enough to mitigate the dangers of a hurricane

- Hurricanes are unpredictable and the fallout they produce goes far beyond wind speeds

- Hurricanes have a major impact on our energy infrastructure and cost the country billions

- One of the best ways to quickly recover from hurricane outage is with a decentralized solar energy network

Why are hurricanes so dangerous?

There are a number of reasons, obviously: high winds, their tendency to drag ocean waters onshore, and certainly their unpredictable nature. But one of the most dangerous aspects of a hurricane is experienced after the storm has passed—and that is extended energy blackouts.

The Dark After the Storm

You may be wondering how a blackout can compare to a natural disaster. Sure, they are often a result of one, but it’s not quite the same as expansive winds that have the power to tear down buildings. Blackouts are much less visceral and their true impact can be unseen by many, but they have an incredible influence on the economy, your safety, and people’s health.1 But before we dive into that, let’s talk about why a giant storm of wind can get away with so much.

Hurricanes are unpredictable. It can feel helpless to combat a natural force that is larger than the state in which you live, with a reach so broad it can be seen from space. That kind of force equates to a number of variables that we don’t yet have the tools to calculate. When the signs show, a hurricane might come in an instant or it might not come at all. And when it does, it’s incredibly difficult to predict what kind of effect it’s going to have. Hurricanes can do so much because there is so little we can do to prepare. And even when we can, it’s difficult to act quickly enough to make a difference.

Hurricanes and Energy

One of the reasons that scientists are pursuing better hurricane prediction models is to better protect our energy.2 Our entire world operates on electrical power. Businesses run on it, employees work through it, and orders are made by technology. Without the energy to operate those processes, billions of dollars are lost. And repairing the energy infrastructure after a major storm is incredibly costly in itself.3 Power disruption for any reason is a concern, but storms account for almost 60% of all major outages.4 In fact, hurricanes are responsible for nearly a trillion dollars in damages over the last 40 years!5

And what about the loss of productivity during the outage? Hurricane Sandy left 8.5 million people without power.6 In the face of an outage, we can’t simply light a few candles and go about our day. Especially with so many more of us working from home, entire industries can be shut down from an outage. On top of that, access to fresh food and crucial medicines are made possible by electricity. If food spoils and medicine becomes inert, it can leave many families in a more dire situation than they were in during the storm. Often, utility companies work tirelessly to restore power, but even then it can take a week or longer to provide electricity to homes again.7 For most people, that’s just too long.

How do we fix it?

We fix it by changing the way we do energy.

In fact, the government is constantly working on this. Our power infrastructure, in most places, is either beyond its initial life expectancy or halfway there.8 Our energy network in America is not in its prime, in other words. But too much of the work to protect against further outages in a storm is focused on reinforcing what we already have.9

Systems designed 50 years ago are not necessarily suited for today. Storms are different than they once were. Climate change has made subtle shifts in the way the forces of nature react.10 On the surface, it seems the same, but these changes can result in vital differences. For example, evidence suggests the shift in the climate has led to less powerful, yet more frequent hurricanes, which can be even more devastating depending on where they occur.11 There is also some research suggesting that as the climate shifts more, the results will vary, leading to even more powerful hurricanes.12 And adding to the growing unpredictability of the storms themselves is the fact that so much more is in harm’s way than in decades past.

It should come as no surprise that the United States (and specifically our hurricane-prone coastlines) have seen an explosion in population and development over the last century. More people and more buildings mean there is more to be lost when a hurricane does hit us hard. One researcher figures that the inflation-adjusted cost of hurricanes in the U.S. alone climbed from close to zero in 1900 to over $130 billion in 2005.13

So, in the face of all of this, we have to ask ourselves: is the answer really to duct tape our existing infrastructure?

Miami Beach (FL) is just one example of how development has put more in harm’s way. (1925-Left 2017-Right)

Source: wildculture.com

Solar’s Role in a Better Approach

Traditional energy is produced by a utility using fuels of some sort (fossil or natural gasses, typically) that are burned to turn massive turbines and generate power. That power is then delivered through power lines to your home through an extremely complex network of wires, transformers, and whatnot. One of the lesser-known drawbacks to this approach is that if something goes wrong with the power source, or any of the major transmission lines, then huge amounts of people are impacted.

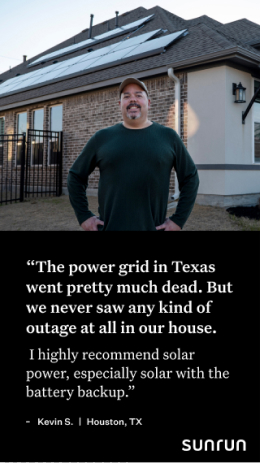

With decentralized power, if the power source is damaged or hampered in some way, not all homes are affected. Currently, the only practical application of this idea is with a solar energy system. The panels sit on your roof and generate power when the sun comes out. When paired with a home solar battery, that energy can be stored for use at night or when power from the local utility goes down.

A VPP drawing power from another community after energy is disrupted

This equates to a very real chance of “virtually” eliminating outages. What usually equates to billions of dollars in repairs and desperate attempts to mitigate power downtime after a hurricane can be corrected in moments with a system built on solar energy.14

Moving in the right direction

We have a long way to go before our energy infrastructure is where it needs to be. But one of the best ways we can do it is by shifting to solar now—as individuals. Many of the problems with traditional energy production, even with other renewable methods, can be solved by decentralizing power production through rooftop solar panels.

We can spread clean energy generation across homes and equip them to store power for later with home batteries. That alone can make all the difference when it comes to not only powering through—but recovering from hurricanes.

Your home energy, customized

- Get your system size and battery details

- Find your solar cost and energy usage

- Learn about the incentives in your state

- 1. Anderson, K. When the lights go out. Nat. Energy 5(3), 189–190 (2020).

- 2. Guikema, S., & Nateghi, R. Modeling power outage risk from natural hazards. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science. (2018).

- 3. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), “Failure to Act: Electric Infrastructure Investment Gaps in a Rapidly Changing Environment,” 2020.

- 4. Mukherjee, Sayanti & Nateghi, Roshanak & Hastak, Makarand, 2018. "A multi-hazard approach to assess severe weather-induced major power outage risks in the U.S," Reliability Engineering and System Safety, Elsevier, vol. 175(C), pages 283-305.

- 5. Mukherjee, S., Nateghi, R. & Hastak, M. A multi-hazard approach to assess severe weather-induced major power outage risks in the US. Reliabil. Eng. Syst. Saf. 175, 283–305 (2018).

- 6. Nateghi, R., Guikema, S. D., Wu, Y. & Bayan Bruss, C. Critical assessment of the foundations of power transmission and distribution reliability metrics and standards. Risk Anal. 36(1), 4–15 (2016).

- 7. Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability U.S. Department of Energy. Comparing the Impacts of Northeast Hurricanes on Energy Infrastructure. 2013.

- 8. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), “Failure to Act: Electric Infrastructure Investment Gaps in a Rapidly Changing Environment,” 2020.

- 9. Edison Electric Institute, “2018 Financial Review: Annual Report of the U.S. Investor-Owned Electric Utility Industry,” pp 52-53, 2018.

- 10. Contento, A., Xu, H. & Gardoni, P. Risk analysis for hurricanes accounting for the effects of climate change. In Climate Adaptation Engineering 39–72 (Elsevier, New York, 2019).

- 11. Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part II. Projected response to anthropogenic warming. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 20, 19 (2019).

- 12. Camargo, S. J. Global and regional aspects of tropical cyclone activity in the CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 26(24), 9880–9902 (2013).

- 13. Pielke Jr., Roger. The Climate Fix: What Scientists and Politicians Won’t Tell You About Global Warming, 171.

- 14. McManamay, Jennifer. “RESEARCH: LESS CENTRALIZED, RENEWABLE POWER A BETTER BET AS HURRICANES INTENSIFY.” UVAToday, 2021, https://news.virginia.edu/content/research-less-centralized-renewable-power-better-bet-hurricanes-intensify. Accessed 15 July 2021